Explore how board game ideas grow from theme, mechanics, or message, and learn how a clear creative focus shapes better game design.

If you ask any creative person what question they get most often, this one will surely be in the top three: Where do your ideas come from? The answer is usually a few confused glances, a shrug, or some mumbled remark about the infinite ocean of the collective unconscious. It’s a difficult question. But in board game design, even if we can’t always pinpoint the source of the initial spark, it’s usually possible to trace back what that small yet crucial element was from which the entire complex game grew. In the following, I’ll go through what the process looks like when a game idea sprouts from theme, when it wants to deliver a message, and what it looks like when it comes from mechanics, and what designers and developers need to keep in mind depending on the source of the inspiration.

Choose a fixed point

Creators of famous artworks often describe how everything grew from a single small idea or thought. Just like in other art forms, game designers also have to choose a starting point that provides a solid foundation for their design. In board game design, every idea begins with a spark, a theme, a mechanic, or a message and that initial choice shapes everything that follows.

Mechanic design

When a game starts with a mechanic, it often builds upon something that already exists. We may feel that there’s an unexplored or interesting combination of familiar mechanisms, or perhaps a relatively new space that lies between the scope of other well-known mechanics.

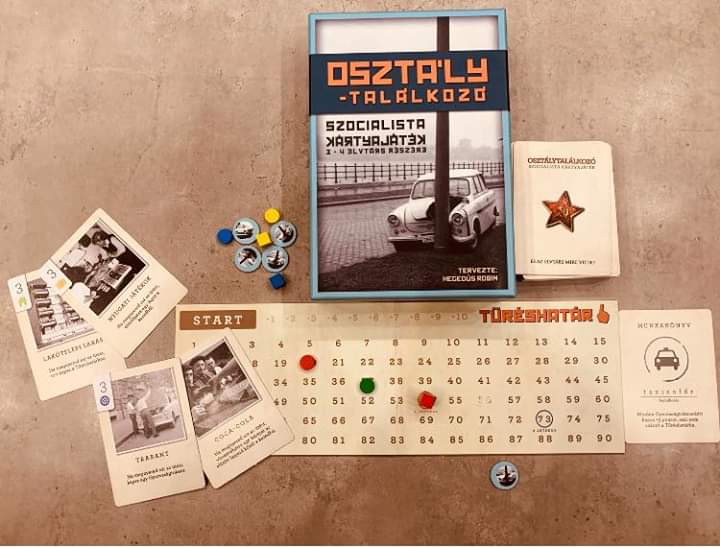

Back in university, I became obsessed with trick-taking games and came up with the idea of a game where players try to win as many tricks as possible, but if they go too far, they’re eliminated. I wanted to combine trick-taking with the main principles of Blackjack – that was the foundation of the mechanical design. Then I looked for a fitting theme and came up with a satirical setting from 20th-century Hungarian history: the socialist dictatorship era, where people gather for a class reunion. The cards featured various possessions, from Trabant cars to Western records and Coca-Cola bottles. Each trick represented a conversation where classmates brag about what they’ve achieved and what they own. The one who “boasts” the most wins the trick and is seen as the coolest. Players count the point values of the cards they’ve collected, showing who was the star of the evening – but there’s also the risk that if you brag too much and cross a certain “tolerance threshold,” you attract the attention of the authorities.

The theme fit the mechanics well, but later we realized it could easily be re-themed into a more universally understandable setting. In mechanical design, this is perfectly fine, since the core is the mechanism, not the theme. The class reunion could just as easily be about superheroes competing in different domains – but if they prove too powerful, people start seeing them not as heroes but as monsters (as many comic book stories have illustrated). In mechanical design, the goal is to find a theme that brings the mechanics to life and draws players into the experience. But sometimes the mechanics come later, when the world itself, not its systems, is what first captures the designer’s imagination.

Thematic design

In thematic design, the designer’s initial intent stems from a desire to immerse themselves and the players in a particular world and let them experience aspects of it during the game. It’s important to emphasize that this doesn’t mean the gameplay itself must be narrative or story-driven (as defined on BGG’s thematic games page); it simply means that the design’s starting idea is rooted in a theme.

The best example of this is Septima. Its starting point wasn’t a mechanic, but the promise of a world: I wanted to create a game where witches are the protagonists, who, despite the townsfolk’s suspicion, use their magic for good. That was the goal – to create that kind of game. The mechanisms had to serve this thematic foundation. Researching benevolent witches and historical healers made it clear that players should gather ingredients from nature to brew potions and heal the sick. The idea also contained the townspeople’s suspicion, which manifested in the game as the Suspicion system, driven by the collective actions of outcast characters.

When working from a theme, it’s worth reviewing familiar games and their mechanics to find those that best bring the theme to life. The stage is already set – now we need structures that move the pieces so naturally that the players “don’t hear the machinery clanking behind the scenes.” If, during design, a mechanic feels forced or too abstract, pulling players out of the world we’ve built, we should look for a more immersive alternative that better serves our original intent. Yet not every game begins with a mechanic or setting. Some games exist first and foremost to say something, to deliver a message.

Communication design

Communication design is the least common of the three, and it doesn’t fit neatly under the other two categories. It’s important to recognize when a game belongs here, because it changes how we approach it. These games don’t aim to bring a thematic setting to life through matching mechanisms – instead, they exist to convey a specific message or tell a specific story. Interestingly, many ancient games fall into this category, as they were created as symbolic representations of moral or philosophical ideas.

For example, the traditional Game of the Goose, where players advance along a linear board according to dice rolls, symbolizes that a higher divinity (the die) determines the path of our lives, over which we have little control, and whose plans are unknowable. But not only ancient symbolic games were made this way – some modern ones also start not from theme, but from message.

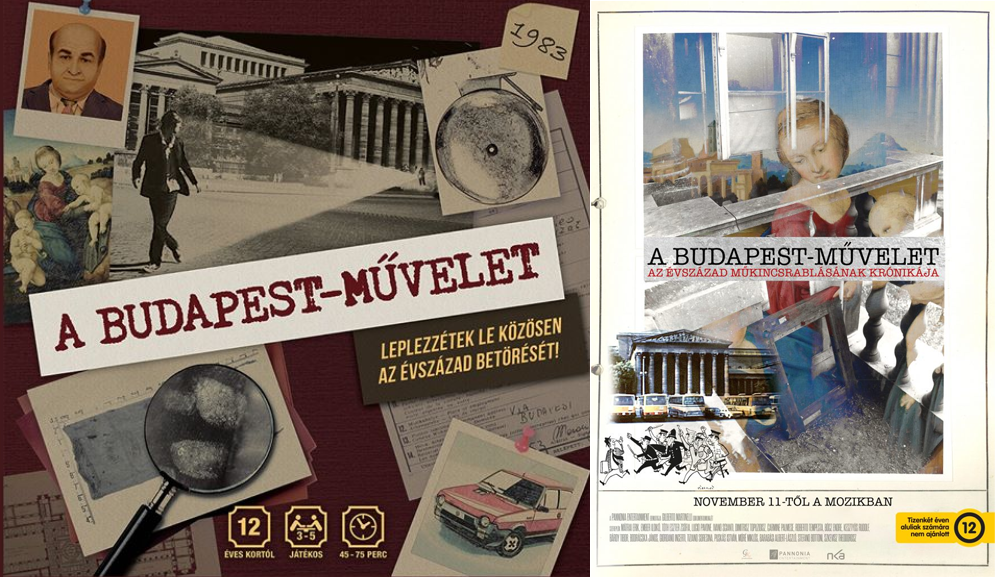

A personal example is Operation Budapest, a small-scale commissioned project created to accompany a documentary film of the same name about the real-life robbery of the Museum of Fine Arts in Budapest. The client defined the design’s starting point and communication goal: to show how European law enforcement agencies cooperated to track down the fleeing criminals and stolen artworks. The game wasn’t a thematic design meant to evoke the thrill of police chases – its purpose was to convey the message of international cooperation, in line with the film’s narrative.

The biggest risk in communication design is that the message becomes so dominant that it overshadows the game itself. It’s essential to ensure that meaningful decisions remain for the players, so they don’t experience the game as a scripted educational exercise.

Keep your goal in sight

There’s a quote often passed around in creative circles – its exact origin unclear – but it has become something of a shared proverb in game design: “Fall in love with the problem, not the solution.” In our case, the problem is the goal we set out to achieve with our core idea: I want to combine trick-taking with Blackjack; I want to make a game where witches are benevolent, nature-connected characters; I want to make a game that highlights the importance of international cooperation.

Later, during development, after many iterations, there will be moments when we feel stuck. That’s when we must ask: What should we change to make the game better? In these moments, we need to look back to where we started – what was the spark, the original idea that made us say, “Yes, this is something I want to make!” That’s our “problem” to solve through design. If the current “solution” doesn’t work, it’s fine to let it go – it’s the goal, not the method, that truly matters.

Whether a game begins with a mechanism, a theme, or a message, every path eventually converges on the same challenge: turning an abstract idea into an experience others can share. What matters is not where you start, but how faithfully you carry that first spark through all the messy, mechanical, and emotional layers of design and playtesting. The origin may differ, but the goal is always the same: to create something that feels alive in the hands of players.