So, you just developed a meaty eurogame, and it’s really good. It’s balanced, fun, looks great… and now comes the hard part: explaining it.

You sit down to write the manual. At first, it feels fine, the rules aren’t even that long. But when people start reading it, everything goes wrong. How are they missing important rules? Page 28 clearly says that Authenticating an Actuator is not a Bonus Action! What is going on?

I know, I’ve been there. Actually, I’m still there, since this became my job. So, to save you some pain, here are 5 tips that will make your rulebook clearer and easier to use.

1) Balance Teaching Power and Reference Power

When the first draft is done, think about the structure of your rulebook. Some parts are obvious (Components, Setup, Table of Contents), but the way you organize the main rules can vary a lot.

A rulebook needs to serve two main purposes:

- Teaching Power: Guiding new players through the game step by step. To maximize this, build up the text in a natural flow, as if you are explaining it. Don’t divert attention with corner cases.

- Reference Power: Letting players quickly look up rules during play. To maximize this, everything related to a topic should be under the same chapter.

The problem is that these two goals are clearly in conflict.

Two Ways to Solve It

- One book that balances both, never letting one completely dominate the other. This is how Voidfall was solved, for example. A good test to see if you have achieved this: Count how many times you write “see page X.” The fewer cross-references indicate a better balance.

- Two booklets: one for teaching, one for reference. Wargame designers use this trick often (see Root for a famous example). It’s more work, but sometimes easier for the reader. This is something I don’t do, but it’s a valid way.

Extra tip: Think of a spread (two pages) as a unit. Readers can easily navigate two pages next to each other until they have to turn them. This opens up possibilities for you to move the sections around and play around with the order of things on the micro-level.

2) Be Precise, Except When Vagueness Helps

I think the following tip only really matters above a certain complexity level, but it never hurts to keep in mind.

- Don’t use synonyms for game terms. If you say “resolve an action” somewhere, then don’t say “take an action” somewhere else. The reader is aware that a human wrote the rules, and they will assume, at all times, that you have made conscious decisions as the author of the text. They will wonder if “take” and “resolve” mean the same thing or if they are deliberately different. Let’s not leave the poor reader hanging!

- Take time to build up the game’s vocabulary. Open a spreadsheet and write a list of complete phrases, with enumerations, like “gain 1 stone” and “gain 1 wheat”. If you put in the work, not only will you feel more confident navigating your own text later, but your proofreader will also love you for it, not to mention the plethora of translators!

At some point, you might be afraid that the constant repetition of terms will make your text robotic and way too distinct from normal, human language. This is a valid concern, but it’s better than confusion. You can still write with some variety, as long as your rules vocabulary is consistent.

When Vagueness is Good

All that being said, you can actually use vagueness to your advantage. Sometimes you don’t want to actually explain a rule, but you want to give some context to your reader about the upcoming chapter, usually in the first sentences or the first paragraphs. For example, when you hit a section off with “Guilds are your main source of income”, the vagueness of this sentence signals to the reader that this is not yet a rule, and they will not assume that it is. This balance between strict terms and soft introductions makes the text more readable.

3) Anticipate Your Audience

When you talk to someone in person, you naturally adjust how you speak. Every group, every situation has its own linguistic register that you unconsciously follow. Writing rules is harder, because you’ll never meet your readers.

Know Who You’re Writing For

- Research: Who will be your players? Experienced eurogamers? A young couple with their first board game? Wargamers? Kids (and their parents)? Keep this in mind from the beginning, during playtests of the game. Consult with the publisher about who the target audience is.

- Test your rulebook: Get feedback from your actual target audience, not just whoever is available. Otherwise, you risk rewriting your text to suit the wrong group.

Accept that your rulebook can’t please everyone. You’ll always alienate someone. That’s okay, but you should at least make conscious choices.

Learn the Traditions of Your Genre

Some rules are “self-evident” to certain audiences, and not to others. For example:

- Do you need to explain what spending a token looks like?

- Do you need to say that an action with a cost can’t be taken without paying it?

- Do you need to define what a card, die, or meeple is?

If your imagined reader already knows, skip it. If not, spell it out.

Extra tip: Registers can be mixed. They are more of a spectrum than clearly distinct categories. A text can be somewhat playful and beginner-friendly, somewhat dry and technical, all at the same time. Audiences for games can intersect, and your audience will be a unique subset.

4) Images Are Rules

For this tip, first let’s take a step back and think about what a board game is and how it is played. It is ultimately a heap of physical objects that players look at, then touch, move, and organize.

The Role of an Image

The rulebook’s job is to name those objects and explain their meaning. For example:

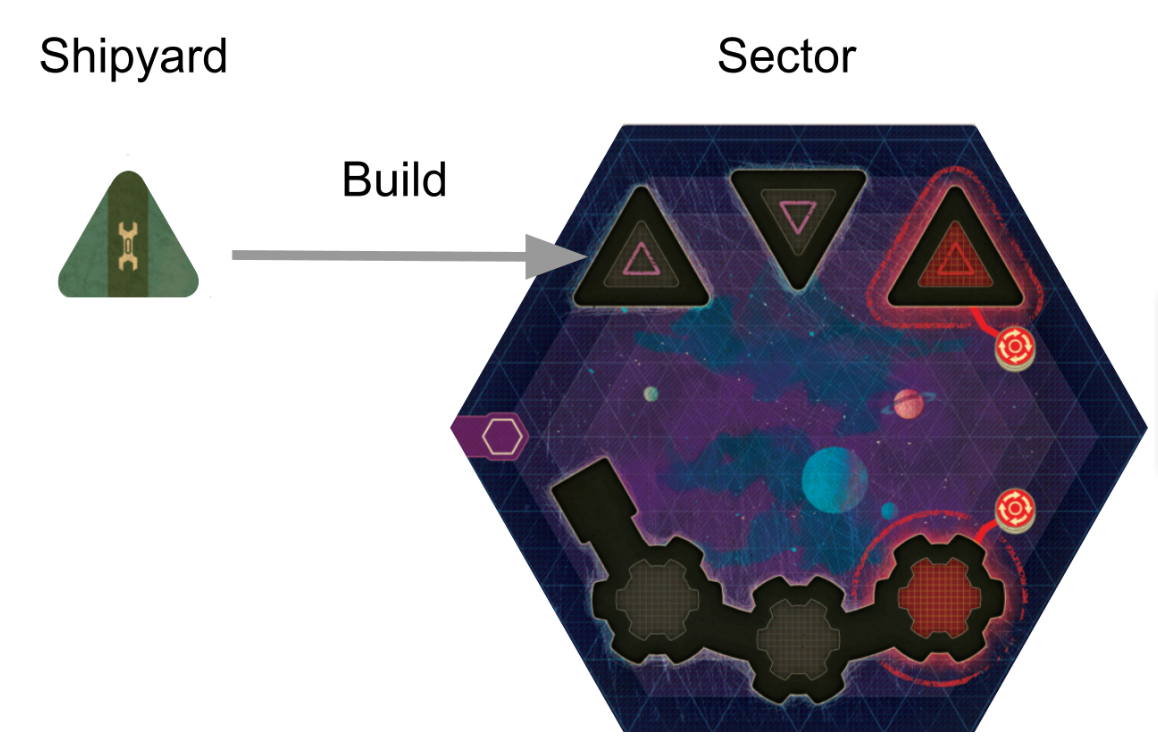

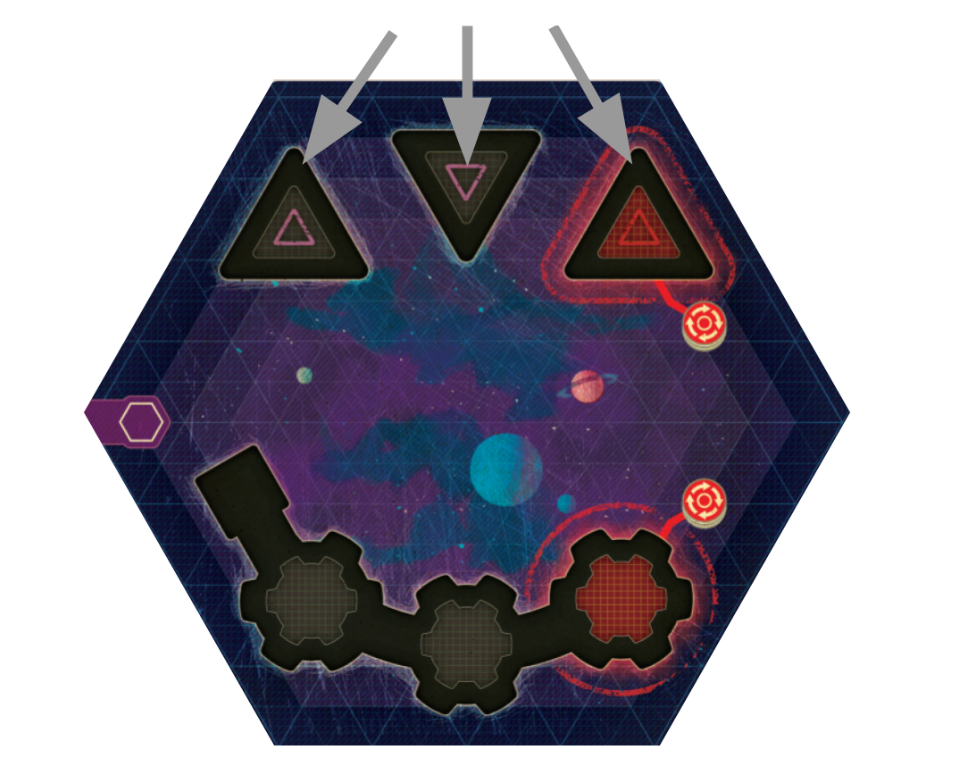

- A green cardboard triangle is just cardboard, until the rulebook says it’s a “Shipyard.”

- A hexagon is just a shape, until the rulebook says it’s a “Sector.”

- Place the triangle on the hexagon, and suddenly you’ve “built a Shipyard in the Sector.”

Notice how, in the above example, you cannot make the connection between “this” and “Shipyard” unless an image directly shows it. Also, notice that it actually doesn’t matter if this is called “Shipyard”, “Dock”, or “Wrench Triangle”. What establishes the rule is the image itself. The image is a rule, or at least an integral part of it.

Images can be More Efficient than Text

We can take this one step further. Not only are images important, but written language cannot even efficiently describe what an image can. When you “build the Shipyard”, there is a very specific place you need to place the green triangle on the large hexagon. It would be awkward to painstakingly describe how three triangular spaces are printed on the large hexagon along one of its edges, and that’s where the green triangles go. You can just point at them.

Images are a chore to make, and it’s easy to say that the graphic designer will do it. But you cannot write the text surrounding the images unless you already know what is on them. Images are a language in themselves. Communicating in images requires a different way of thinking. Hone this skill. You will have a hard time writing a rulebook without understanding how images convey meaning.

5) Use the Appendix Wisely

Sometimes it’s hard to decide what belongs in the main rules and what can go into the appendix.

General Principles

We can put rules in 3 categories:

- Definitely a main rule. Rules governing components or modules of the game that all players will encounter in every game (like a main board worker space, or the general structure of an action card).

- Definitely belongs to the appendix. A unique ability of a single card that is drawn from a deck at random, meaning that only one player will encounter it at most.

- Something in between. A repeated ability on cards.

To sift through the last category, you can use two indicators:

- If it is very likely that multiple players will see an ability every game, it’s better to be mentioned in the main rules.

- If you need to repeat a rule in the appendix so many times that it significantly extends the rulebook, bundle it into a main rule chapter and reference it instead.

Be Thorough When Writing the Appendix

- Include minor questions.

- Discuss unique interactions between abilities.

- Be especially rigorous with your language.

Yes, your publisher may complain about page count. But 4 extra pages is a tiny cost compared to the benefit of preventing rules arguments. If you’re worried about a “scary big” rulebook, publish the appendix as a separate booklet.

—

Final Thoughts

Writing a rulebook is hard. You’re not just explaining rules, you’re teaching, clarifying, anticipating, and preventing arguments. But if you follow these tips, you’ll save your players hours of confusion and yourself a hundred angry forum posts. :)

Take care,

Mityu